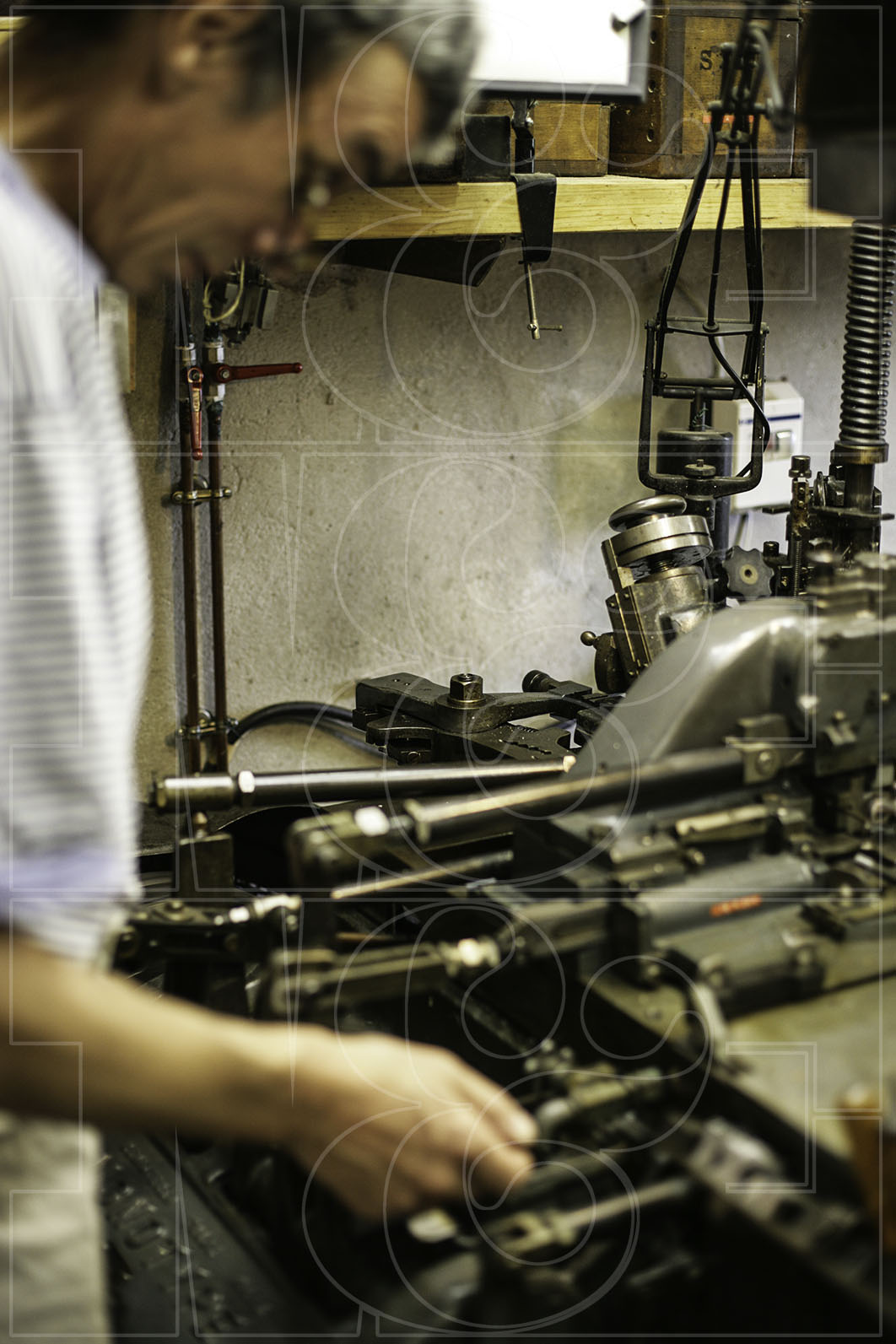

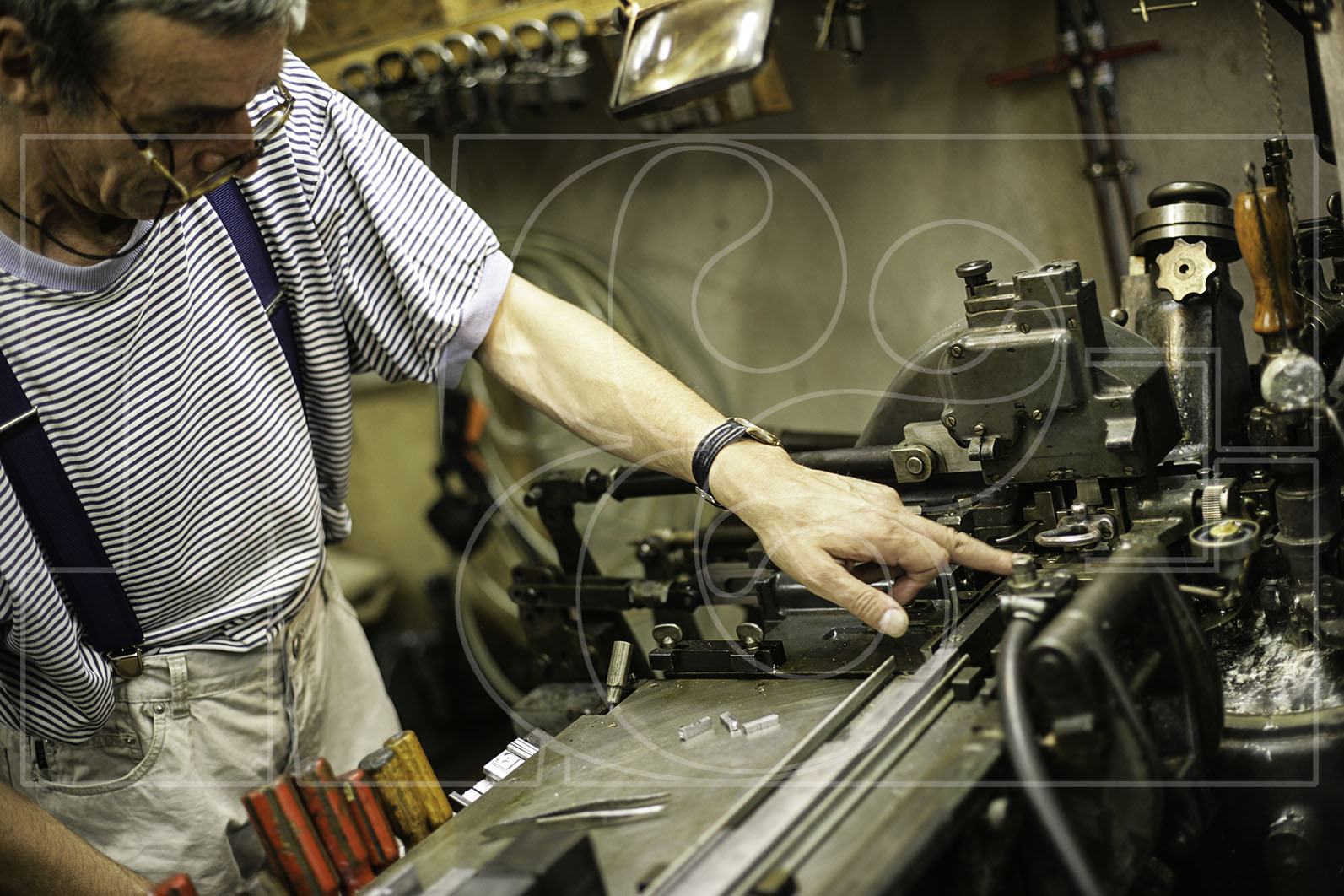

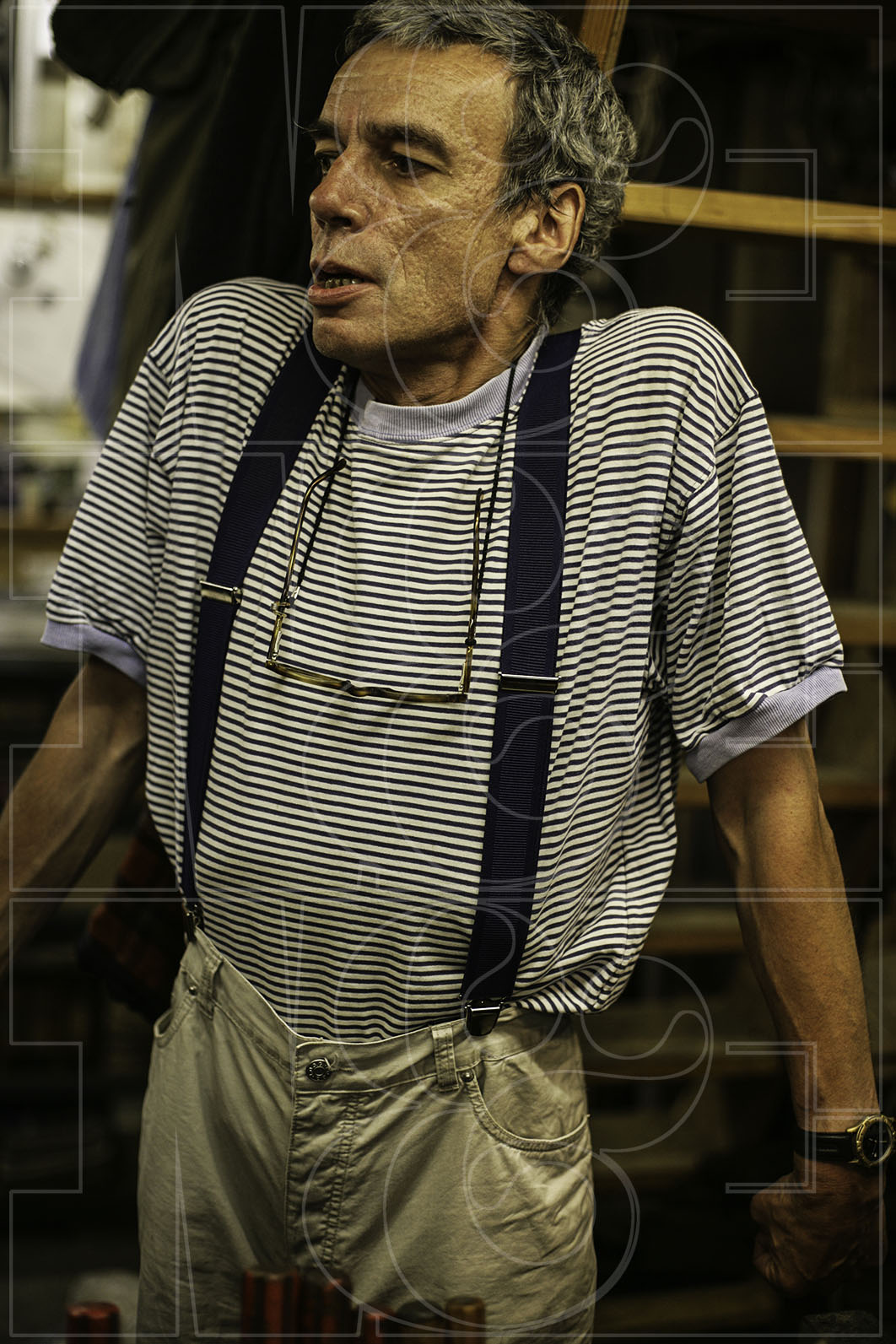

My big brother, David, who’s spent the last thirty plus years living in France, took us to see Thierry Bouchard’s letterpress printing operation in Losne, right next to the Saône River in Burgundy, France. We suspect the only one more thrilled than us was Thierry, his exuberance in showing us his craft bridging my language gap, and we spent a wonderful afternoon viewing his anachronistic machines demonstrated to us by a true craftsman. Like a French Mark Twain, Thierry set type in hot lead, lovingly spacing and feeling the letters. It was a glimpse of an era gone by, revealed to us by a man whose time was also in short supply. Thierry died less than a year after our visit, in 2008, taken by cancer. And with him, his craft passed from this earth.

Click to Enlarge

The man was in the image of his art: dark, secret, protean. His mania: accuracy, that of the goldsmith, the luthier, or better, the first violin. Obviously he needed to be intransigent, grappling with the innumerable demands of his art. Also generous to excess, quick to discern the essential – the tiny detail or the big idea – and to share it. He had a superior intelligence, exasperated by the inertia of matter and the ineptitude of his colleagues. He quarreled with everything, impatient of all obstacles, jealous of his independence, eager to succeed with a work or with a man, both having become dear to him. Artist to the tips of his fingernails, with a sense of taste and skill that illuminated, and left speechless …

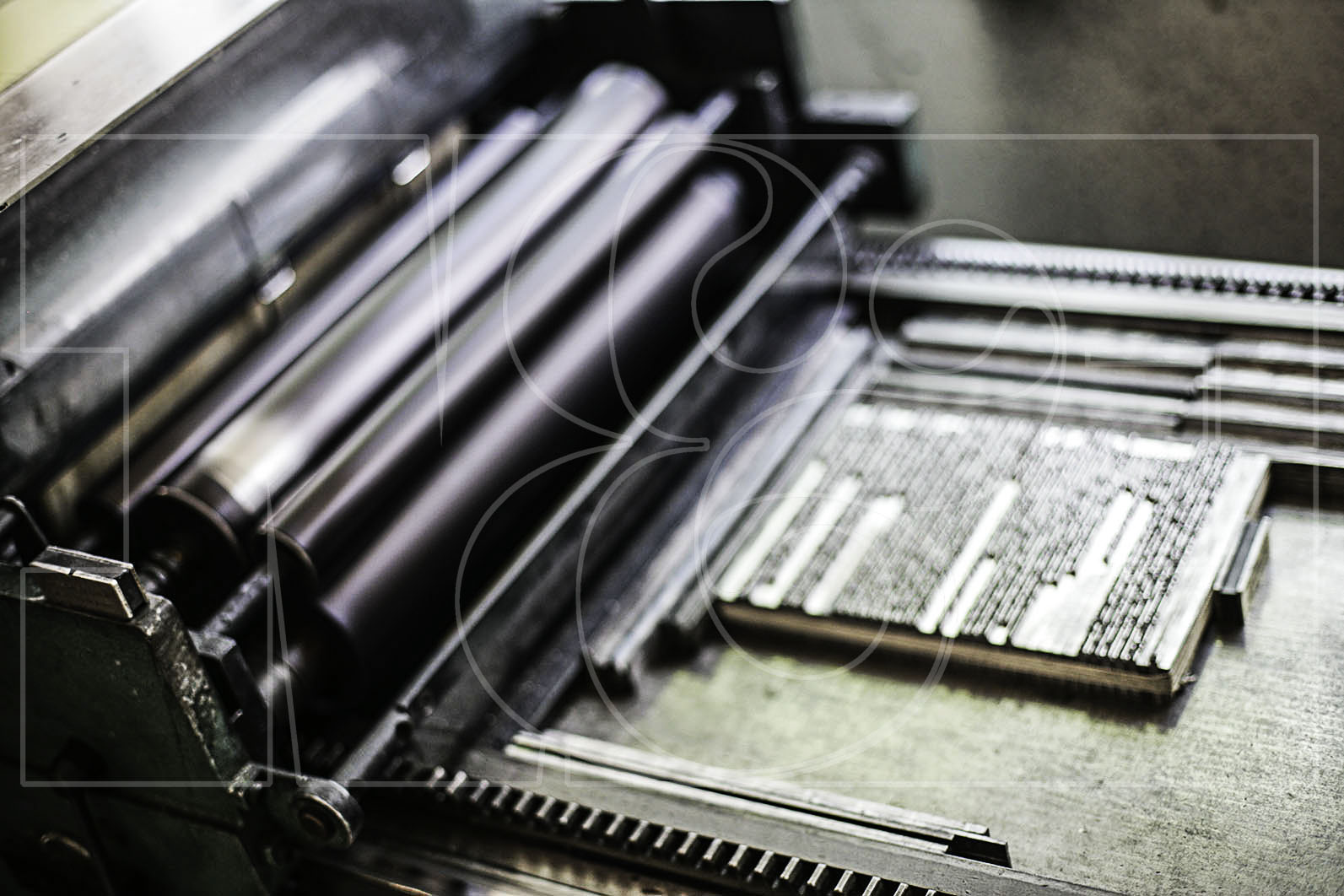

Born in 1954, disappeared in 2008, Thierry Bouchard was one of the last great printers-editors-typographers. On his presses, based in Losne, Burgundy, he created one of the most beautiful sets of books that could be dreamt of, joining the science of casting and fonts, and prints, papers, and formats, to an enlightened commitment to contemporary literature, essentially poetry, which he himself would also author, discreetly. He produced 115 books for his own publishing collections and almost 200 in the form of co-publications or printing for his editor friends – who bear the names Butor, Bonnefoy, Puel, Juliet, Du Bouchet, Nelli, Hubin, Novalis or Segalen, among others – and those of artists as prestigious as Zao Wou-Ki, Pierre Alechinsky, Bram Van Velde, Antoni Tápies, Olivier Debré, André Marfaing… Large illustrated works or small books of an extremely elegant and meticulous workmanship came out of the hands of this exceptional craftsman whose work, undoubtedly, will leave a lasting mark on contemporary bibliophily.

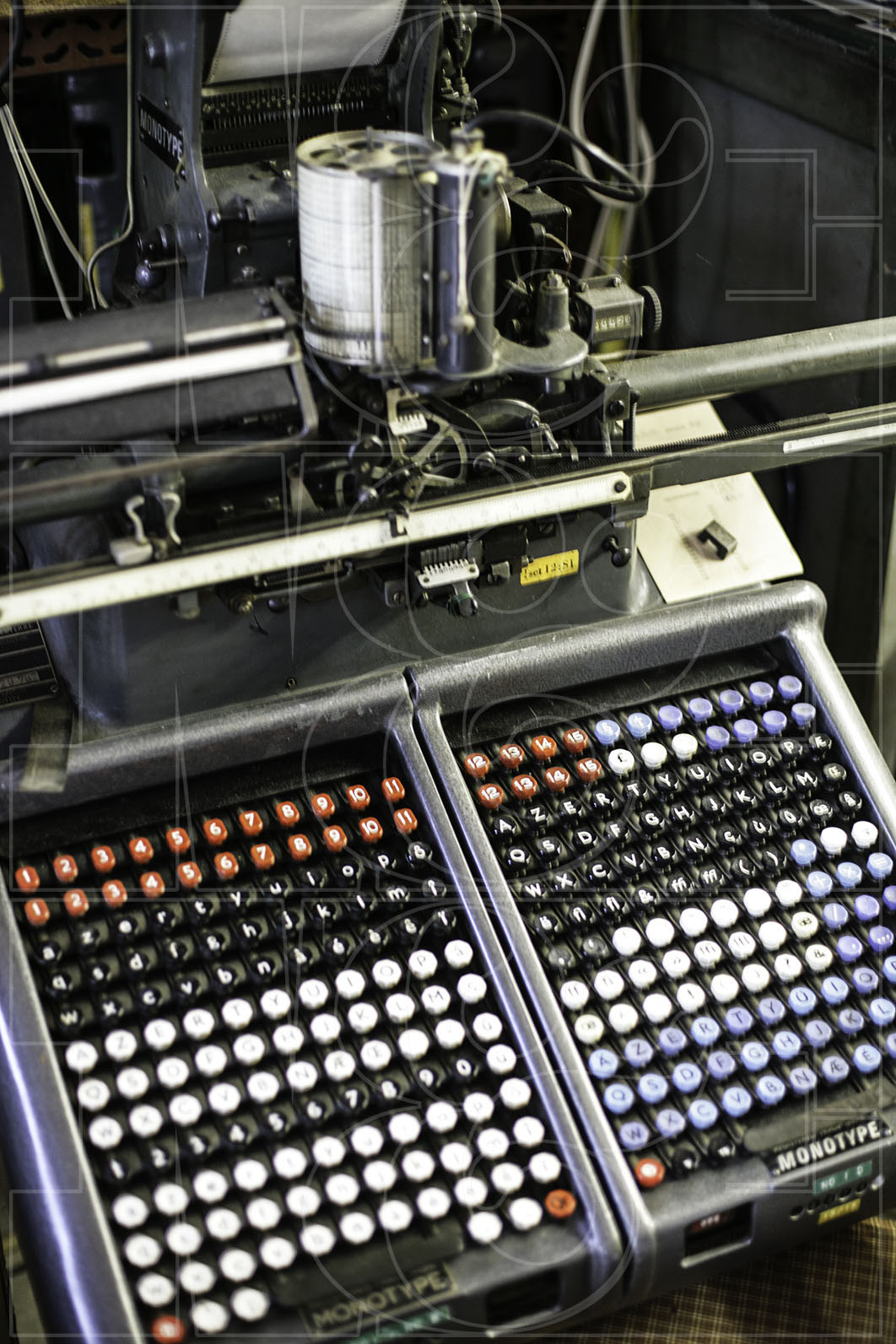

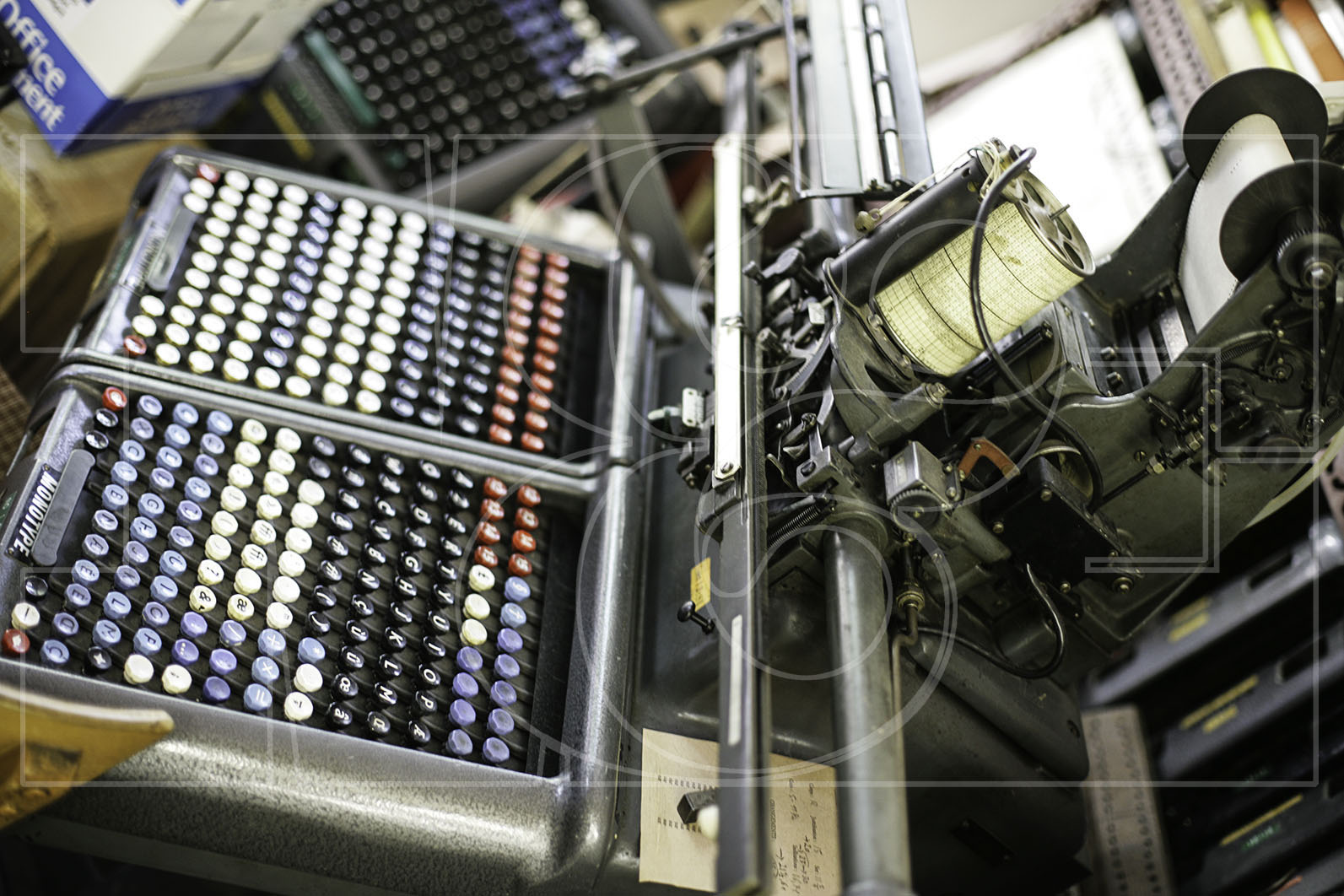

Working with Thierry on the current book was half hard-learning, half ecstasy, always astonishing. The man was burning; fire had taken hold of his heart, a black fire like the furnace in which the lead of his smelter was seething. The final astonishment was to see fresh pages, so clean, such luminous precision, like the new, sparkling characters coming out of such heat – the suffering passion of the profession – clattering and clanking out of the vibrating monotype machine. Suffering from not suffering the slightest waste or the smallest fault of fingering, suffering from never having enough time or enough room in the workshop to store his machines and tools. Suffering finally from being himself alone within the limits that such an art – so vast – imposed on him.

Among all his lessons, I hold this one for the main one: that the arts of the book are saturated by time, the time of the human presence at work since the beginning of the ages. “Those people!” he cursed, exhausted, “they think a book is made overnight!” Think, calculate, plan; try, correct, do and redo; think again, resume everything from scratch; take your time to take the time necessary to do what is necessary to approach the desired perfection… Thierry had the time to produce more than 300 books on his presses since 1974, each of rare distinction. In the end, it was not so much time that he lacked – but rather the times which were unfaithful. He had long known that the ground on which he had built his art and his passion was slipping away beneath his feet. The lead arts had died before him; the time of the beautiful book was over. Without work – and no longer able to work – he spent his final days making collages.

– David Mus, translated from the original French